Smashing the silk ceiling: Anna Maria Garthwaite

3 mins to read |

If you walk down Princelet Street in Spitalfields, you’ll find a blue plaque on what used to be the home and business premises of Anna Maria Garthwaite.

But she wasn’t just a designer of silks – as per the plaque - she was THE silk designer of the mid 18th Century. Her patterns were worn by the richest and most influential women in Britain, Europe and America.

But how did a vicar’s daughter from Lincolnshire manage to succeed in a male dominated profession? And what brought her to Spitalfields?

Silk weaving in Spitalfields

Spitalfields owes its name to the long gone medieval priory and hospital of St. Mary Spital.

By the early 18th Century the fields had given way to a rapidly expanding suburb of immigrant communities, including the Huguenots (French protestants fleeing religious persecution). They were England’s first refugees - the name derived from the French word réfugié - meaning a person seeking refuge.

Historians estimate that as many as 50,000 Huguenots came to England, with 20-25,000 settling in London. One of the largest communities was in Spitalfields. They are remembered today in the street names: Fournier Street, named after George Fournier, and Fleur de lis Street.

But if you walk along Spitalfield’s Georgian streets, you may notice wooden spools hanging down from the upper floors.

That’s because the Huguenots were famous for silk weaving, and many of the silk weavers settled here. Several of the restored Georgian townhouses once housed the richer silk merchants and master weavers.

Why Spitalfields? It already had connections with the cloth trade and - being outside the City walls and its jurisdiction – it was beyond the reach of the City Guilds and their restrictive practices. By the time Anna Maria moved here Spitalfields was the heart of the silk weaving trade in London. Spitalfield silks were known around the world, and widely exported to Northern Europe and Colonial America. It was a natural choice for a silk designer.

But when she moved here with her older sister in 1728, the master weavers and designers were male and French. Anna Maria was neither. How did she manage to succeed in a man’s world?

Becoming THE silk designer of Spitalfields

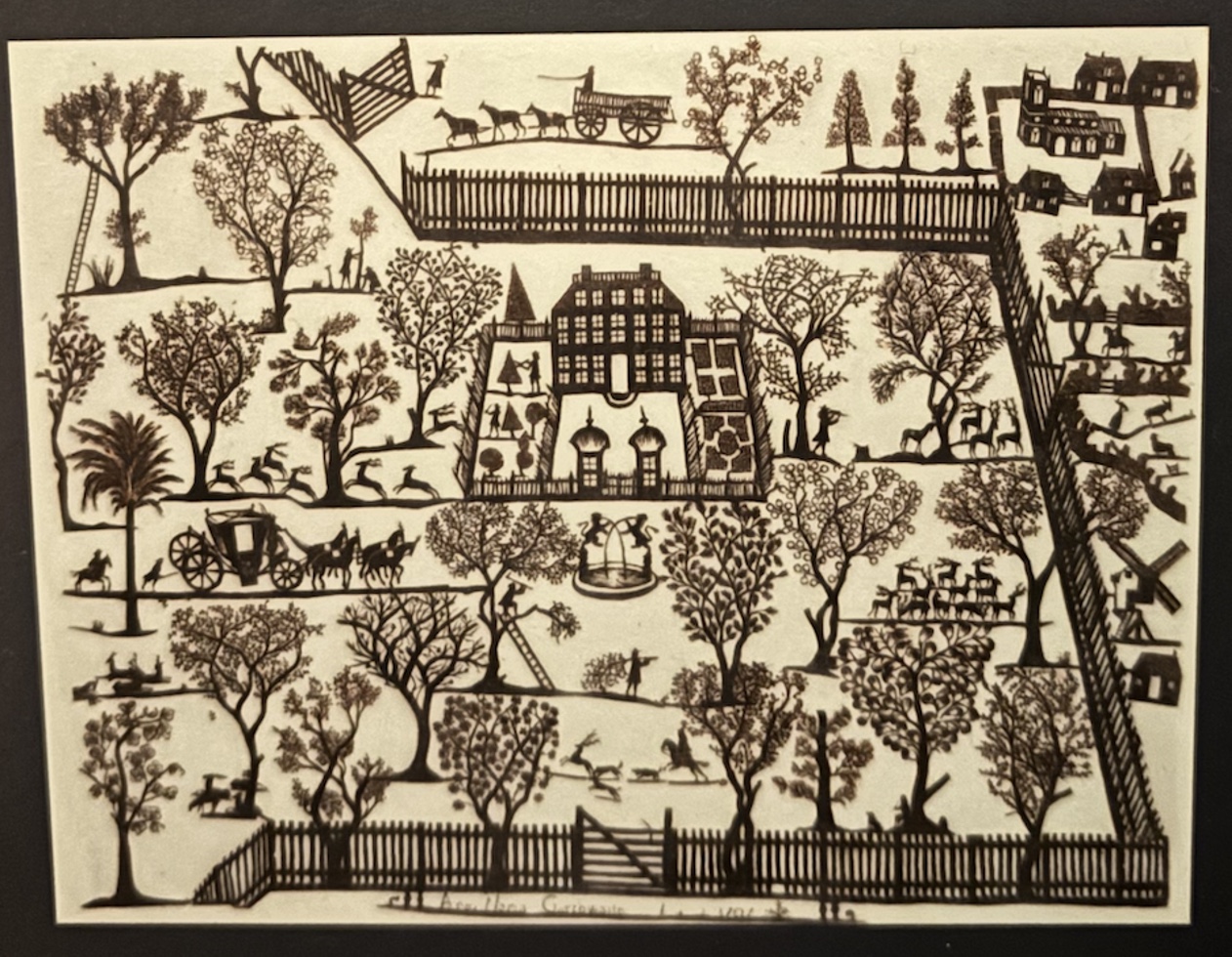

We don’t know when or how Anna Maria developed her talent, but it is unlikely that she had any formal training. However, as this papercut illustrates, she was artistically talented.

And, by the time she moved to Spitalfields in her early 40s, she had managed to work out how to use her artistic talent and turn it into an industrial product. As one historian put it – “She treated the loom like a canvas”.

But wasn’t this a bit of a gamble? How did she overcome male prejudice? While historians do not know for sure, it is thought that some of her designs were sent to London before she moved here, and may well have been shown to the silk merchants and master weavers. She is said to have signed her work with her initials, so they would not have known she was female. Or she may have used a male agent. However she did it, they clearly liked what they saw.

Anna Maria moved to Spitalfields, and the rest is history.

Anna Maria lived there until her death in 1763, aged 75. She was buried in Christ Church Spitalfields.

During her lifetime she created hundreds of designs. Several of her original designs in watercolour are in the V&A and silks based on these designs have been identified in portraiture and costume collections worldwide.